The Rushdie Narrative

On Knife and the crumbling ground beneath the feet of free speech

June 2024

RUSHDIE, to his credit, didn’t want to write this book. He thought fiction would be the way to put the violent bullshit behind him. But when he started to recover from a knife attack that half-blinded and almost killed him in August, 2022, he returned to some notes for a novel to follow up Victory City, his twenty-first book, published during his convalescence. “The notes all just looked stupid,” he told Fresh Air in April. “I just thought, this is all silliness, you know, for me to try and write one of these stories right now… People would think, what’s he doing?”

So he wrote Knife instead. It tells the partial story of how a young New Jersey man called Hadi Matar failed to assassinate him onstage at the Chautauqua Institution’s summer arts festival in upstate New York. It’s partial — and hobbled — for a few interesting reasons. First, Rushdie prefers not to give his would-be killer any rhetorical oxygen. He made a decision not to meet him in jail, so he refers to Matar throughout the book as “A.”:

My Assailant, my would-be Assassin, the Asinine man who made Assumptions about me, and with whom I had a near-lethal Assignation… I have found myself thinking of him, perhaps forgivably, as an Ass.

He also refuses to let Matar pull him back to the Dark Ages of the 1990s and early 2000s, into the long shadow of a death sentence pronounced by the Ayatollah Khomeini for several blasphemous but hallucinatory pages about the Prophet Mohammed in the author’s fifth novel, The Satanic Verses. The old ayatollah never read the book. But what he heard about it offended him so grievously that he promised blessings and riches to the soldier of Islam who would assassinate its author. Khomeini died a few months later, but a fatwa can’t be rescinded, and student groups and other foundations in Iran raised millions of dollars to support Rushdie’s prospective executioner with money and land.

So Rushdie had to live like a fugitive in his adopted hometown of London. A grudging Thatcher government provided an armed security team, once it determined that Rushdie was not just a subcontinental inconvenience but a symbol of Western freedoms. The security guards moved him fifty-seven times during one five-month period. He would pop up with little notice at book events, then slip out as fast as he could. The New Yorker wrote in 1995 that Khomeini had made him the most famous writer on earth, simply because most of the English-speaking world, most of the Muslim world, and most of the Indian population knew his name. Translators, booksellers, and some publishers of The Satanic Verses lost their lives or were seriously injured in attacks in the years after its international publication, and British intelligence would foil six credible murder attempts on Rushdie.

This shadow life ended in slow stages, after the mullahs in Iran tried to distance themselves from the fatwa, in 1998, and after Rushdie moved to New York, where he started to become a visible writer again. “The only way I could stop looking, to others, like some sort of walking bomb, was to behave… as if there was nothing to be frightened of,” he writes in Knife. By 2002 he felt safe enough to let his security team go, and for the next two decades he led a prolific, unhidden, and fairly brilliant career. “One of the annoying aspects of what happened in Chautauqua,” he writes, “is that… it has dragged ‘that’ novel back into the narrative of scandal. But I have no intention of living in that narrative anymore.”

Good. But he announces in the first pages that he wants to understand A., and so do we. Rushdie makes it clear that Matar came to upstate New York chasing an illusion — an imago, a figure of hate — without having read more than a few pages of the blasphemous work, a lot like the Ayatollah himself. In fact the firmest reason Matar could articulate in a post-arrest interview with the New York Post is that he “didn’t like” Rushdie because he found him “disingenuous.” You can almost hear Rushdie laugh. “My strongest feeling, after reading his remarks,” he writes, “was that his decision to kill me seemed undermotivated.”

Every reader of Knife will agree, since a main reason to read the book is to learn about Matar’s motivation. Was he really a lone wolf, as the sketchy public evidence lets everyone think, did he hope for some residual blood money, or was he an agent of Tehran?

Rushdie decides not to find out. We hear about his domestic debates with his wife, the poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, on whether to visit Matar. She discourages him. He resolves to write a work of fiction after all, by imagining the fundamentalist “A.” in a made-up dialogue with the experienced, Muslim-born atheist.

The dialogue, in itself, is good:

Let me ask you something about your beliefs. Do you believe that everything that comes from God is sacred? Or, another word, holy?

Yes. Of course. The Word of God is holy and so are His deeds.

The gift of life is a deed of God, would you agree?

Yes.

Then how is it right for a man to take away what God has given? Is that not for God to decide?

You are trying to confuse me. I see it. You are using tricks as a devil does. You don’t even believe in God. An atheist is the lowest of the low. You don’t deserve to talk to me. You are not my equal.

In this chapter we get to watch Rushdie wrestle with ideas that have obsessed him since the attack, and the conversation is well shaped and not too long. (Knife itself runs to about 200 pages.) Rushdie is also sharper than most of his critics about political Islam, since he’s been a victim of the variety that has radiated from Tehran since 1979.

But Matar flew to Lebanon in 2018, where he spent time with his father in his family’s village of Yaroun, on the southern border near Israel. He returned to his mom’s basement in Jersey in a different frame of mind, humorless and apparently sympathetic to Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. His mother told the New York Post last year that she felt disturbed by this transformation, that she’s disowned him since the attack. So the assailant’s story has yet to be told. If he turns out to be a misguided American kid who was radicalized on YouTube after a quick trip abroad, then Rushdie has a point — the story’s tedious. But the Department of Justice has investigated Matar’s visit to that Hezbollah-rich region of southern Lebanon, and his trouble with US law may not involve a simple state trial for attempted murder; he’s potentially facing a federal terrorism charge, too.

The dialogue in Knife mentions his visit to Lebanon, but adds no fresh information, and a sensitive reader may suspect that one of the world’s greatest writers has decided not to spend time on a shoe-leather investigation into his own near-death experience so the Feds can do their thing.

§

A LOT OF PEOPLE will hate the sound of Rushdie letting the “Feds do their thing.” I’ve phrased it that way on purpose, to hint at a growing sense of resentment against him. Before the fatwa he was a faithful member of London’s anti-imperialist Left, but his political trajectory in the meantime has disappointed a number of old allies. Not just 9/11, but also the Mohammed-cartoon wars in Europe, which culminated in the bloody execution by al-Qaeda gunmen of twelve Charlie Hebdo cartoonists and staffers in Paris, have sharpened rather than dulled his mind about the Islamist violence. After the 2015 shootings, PEN International made a point of giving Charlie a Courage Award, and a half-dozen writers objected. They said the magazine’s lowbrow cartoons were too crude and Islamophobic for such a distinction. Rushdie — a former PEN America president — reminded the protesting writers that PEN is a free-speech outfit, that Charlie had made brutal fun of Islam far less often than it had of the French government and the Catholic church; and that butchered cartoonists in Paris were not to be ignored. “It was a bitter quarrel,” he writes in Knife. “Friendships were broken, including some of mine, because I thought, and still think, that failing to stand by our colleagues who had been slaughtered by Islamist terrorists for drawing pictures was a morally confused thing to do.” The list of protesting writers grew, but Rushdie’s tweet making fun of the original six, which I saw in real time, stands as one of the memorable pleasures of the old, anarchic Twitter. “Just 6 pussies,” he wrote. “Six Authors in Search of a bit of Character.”

Rushdie seemed to move to the right, on a literary-political scale; but did he move or did the balance of the whole thing shift? Free speech and resistance to religious fundamentalism were both easy causes for the Left when Khomeini pronounced his fatwa in 1989. Now both positions are “problematic,” for one weird reason or another. To me it’s obvious that if left-leaning thinkers give up their position as reliable defenders of free speech to dangerous assholes on the Right, it will be a profound and irresponsible abdication; but what’s less obvious is that a talent for interpreting different shades of political Islam has never been a strength among literary people in Europe or the United States, and the War on Terror closed up whatever curiosity they may have possessed.

An important lesson of the Rushdie Affair was therefore lost: we failed to recognize how the Islamism radiating from Tehran since 1979 has been tangled up, quite cynically, with anti-imperialism and a hot-tempered but thoroughly dishonest left-wing liberationism. Khomeini found that mixing Islamist ideas with anti-Western rhetoric in the 1970s was a good way to win crossover support from traditional villagers as well as from Marxist intellectuals, and he successfully hijacked powerful leftist feeling against the Shah. Marxists and communists who went along with his revolution found themselves quashed and sidelined a few years later, during a brief civil war, and the mullahs have unsurprisingly failed to turn Iran into a socialist paradise (never mind a republic) ever since. On the other hand, Khomeini’s revolution has served as a model and a beacon for some of the most reactionary and violent Islamist movements in the world, from Indonesia to Gaza, and the anti-colonial rhetoric that some of these groups bolt onto their religious fervor is no kinder to their actual constituents than the original. But there seems to be no understanding of this betrayal on the Left, no desire to craft a fine-toothed argument, no memory of when, or how, Iranian leftists were had.

Rushdie can’t ignore these things. His memory is undiminished. Frightened Westerners as disparate as Jimmy Carter and Germaine Greer criticized him at the time for offending Muslims in The Satanic Verses, to their own enduring dishonor — Carter’s embarrassing think piece was even called “Rushdie’s Book is an Insult.” Plenty of people supported the novelist in 1989, but whole segments of India and Pakistan and “the South Asian communities of Britain” turned against him and never turned back. Rushdie describes it as a lingering source of grief. He dissolved this pain by embarking on a “defense of free-speech principles, a much larger subject than the defense of my own work,” and on these principles he rarely puts his foot wrong:

I can remember being in the garden of our house as a child in the 1950s, listening to my parents and their friends laughing and joking as they discussed everything under the sun, from contemporary politics to the existence of God, without feeling any pressure to censor or dilute their opinions . . . These settings were where I learned the first lesson of free expression — that you must take it for granted. If you are afraid of the consequences of what you say, then you are not free. When I was making The Satanic Verses, it never occurred to me to be afraid.

Sometimes he does put his foot wrong regarding Gaza. In May, during a publicity round for Knife, he suggested to the German Bild Zeitung that a Palestinian state would be ruled by Hamas if it consolidated now. I disagree. If Hamas is not destroyed — or sidelined, or neutralized — it may continue to rule Gaza alone as an Iranian client, like Hezbollah in Lebanon. But free-thinking Palestinians in the West Bank are under no obligation to pretend they respect the Islamists, and I doubt the Islamists can take over a whole state, even if Israel’s war has increased support for them as symbols of resistance. (I still want a two-state solution, and peace in Gaza, for the record.)

But in the same interview he also wished student protesters could express a more obvious awareness of these basic politics. “I would just like some of the protesters to mention Hamas,” he said with a mild ironic grin. “Because that’s where this [round of violence] started… It’s very strange for a young, progressive, student politics to kind of support a fascist terrorist group.” He added that most students just want the violence to end, and no sane person can disagree. But history will show that a lot of young, Western protesters did support Hamas and Hezbollah, or their strategic talking points, thinkingly or unthinkingly, and Rushdie is right about them. It’s very strange.

I want to be a wholehearted fan of Knife, but parts of it are boring — New York–glamorous and Ralph Lauren–chic. Rushdie spends dozens of pages describing his blissful Manhattan existence with Ms. Griffiths to contrast the horror of the attack. He even sets it up as a challenge, reminding the reader that happiness is a topic notoriously avoided by writers, since happiness, in Henry de Montherlant’s description, writes in “white ink on white pages.” It does in Rushdie’s book, too. Parts of it feel like an Oscar speech, an obligatory thank-you note to his wife, her family, his agent, all his excellent friends. I wanted less of that and more substance around Matar, precisely because Rushdie — of all writers — could vivisect the real man’s motivations. In 1989, without knowing it, an aging ayatollah shoved the youngish novelist into the center of a civilizational tension that would puzzle and define the first part of the twenty-first century; and at the Chautauqua festival in 2022 a useful idiot from New Jersey hinted at the baffling number of people who still can’t let it go.

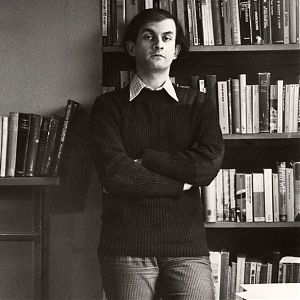

Michael Scott Moore

Rafts of the Medusa

Why every day on the Mediterranean is a new scandal for Europe. For both Foreign Policy and Die Zeit.

California’s Attempt at Land Reparations

How land seized from a Black family 100 years ago may be returned. The Bruce’s Beach story from a hometown angle, for The New Yorker

Day of the Oprichnik, 16 Years Later

The novelist Sorokin, the president Putin, his man Dugin, and the war in Ukraine. For n + 1.

The Rushdie Narrative

Knife and the crumbling ground beneath free speech

There Must Be Some Way Out of Here

An essay on Bob Dylan, “All Along the Watchtower,” and Somali pirate captivity.

That Mystic Shit

The life of Lou Reed in two biographies

Cambodian Seafarers Talk About Pirates

Mike visits Cambodia for The New Yorker to talk about a harrowing shared experience in Somalia

The Muslim Burial

Cambodian hostages remember digging a grave for one of their own. A sequel chapter to The Desert and the Sea

The Real Pirates of the Caribbean

Adventure journalism in Southern California. A travel essay for The Paris Review.

Antifa Dust

An essay on anti-fascism in Europe and the U.S., for the Los Angeles Review of Books

Was Hitler a Man of the Left?

A book that helped Republicans in America lose their damn minds.

Ghosts of Dresden

The Allied firebombing of Dresden in 1945 destroyed the baroque center of what Pfc. Kurt Vonnegut called, in a letter home from Germany, “possibly the world’s most beautiful city.”

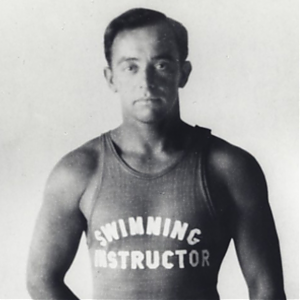

George Freeth, Biographed

The first academic treatment of America’s surf pioneer. Also, was Freeth gay?

It’s Called Soccer

Americans live on what amounts to an enormous island, defended on two shores by the sea, and we’ve evolved a few marsupial traditions that nobody else understands.

Tilting at Turbines (in the Severn River)

The morning was clear and cold, with frost on the church steeple and the cemetery grass. I had a quick English breakfast at a white-cloth table, in my wetsuit, and drove to Newnham, a village on the Severn River in Gloucestershire, parking near the White Hart Inn.

The Curse of El Rojo

I’d packed the car lightly — a bag of clothes, a bag of cassette tapes, a backpack of books, a few essential tools.