One Hundred Years of Hanging Ten

An early excerpt from Sweetness and Blood, about a surf pioneer from the author’s hometown

July 2007

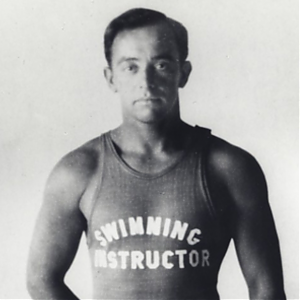

The George Freeth memorial in Redondo Beach is a salt-bitten bust of a lifeguard in an old-fashioned swimming vest, gazing with the stoicism we expect from early surf heroes into the deep mysteries of a concrete parking garage.* His back is to the Redondo Pier. Locals jog or skate past this memorial without noticing the plaque, which reads, “First Surfer in the United States,” and then relates the story of how Freeth was paid by Los Angeles real estate and streetcar magnate Henry Huntington in 1907 to lure people to Redondo Beach to watch a new kind of athlete trim the waves. “George Freeth was advertised as ‘The Man Who Can Walk on Water,’ “ according to the plaque. “Thousands of people came here … to watch this astounding feat. George would mount his big 8-foot-long, solid wood, 200-pound surfboard far out in the surf. He would wait for a suitable wave, catch it, and to the amazement of all, ride onto the beach while standing upright.”

The memorial is outdated: Freeth was only the first celebrity surfer in America. The first men on record to surf North America are now considered to be three Hawaiian princes who noticed that waves at the mouth of the San Lorenzo River in Santa Cruz were up to snuff. Jonah Kalaniana’ole and David and Edward Kawananakoa shaped boards from local redwoods and hauled them out to the beach one day in 1885. “The young Hawaiian princes were in the water,” a local paper wrote, “enjoying it hugely and giving interesting exhibitions of surfboard swimming as practiced in their native islands.”

But Freeth, a haole with one Hawaiian grandparent, helped rescue stand-up surfing from the Christianized sickness of 19th century Hawaiian culture, and he brought it to Redondo Beach. He had won fame on the islands as a talented young swimmer but was ambitious to see the world. After he taught an avid Jack London to surf in front of a hotel at Waikiki — and after London wrote up the exotic art of “surf-bathing” for a magazine in 1907, describing Freeth in syrupy prose as a “handsome brown Mercury” — the young man asked for a letter of introduction. London obliged, and by July 1907, Freeth was bound for North America.

Redondo Beach in 1907 was declining as an industrial harbor, and most of California’s coastline consisted of wind-swept dunes. But wealthy men like Huntington wanted to develop. The Hotel Redondo had gone up in 1890, and a new arm of Huntington’s light-rail line, the Pacific Electric, already stopped at Redondo Beach.

“When I studied the place, and saw its attractions, the beautiful topography it possessed, those terraces rising in harmonious degrees from the sea, I determined,” Huntington wrote, with a real estate man’s instinct for anticlimax, “that it presented such features as should make it the great resort of this region.”

Huntington had competition. In 1904, a cigarette mogul named Abbott Kinney had announced plans to build the “Venice of America,” a gimmicky village with a network of canals and bridges and a flock of gondoliers who would pole tourists around in front of kitschy mock-European storefronts. It would come with a saltwater public pool under an arched glass ceiling and a Coney Island-style pier loaded with rides.

Huntington countered this vision of Oz in 1905 with a three-story pavilion in Redondo Beach, decked out with Moorish arches and flag-topped golden domes. But he noticed that people were wary of the ocean. Most L.A. residents in those days preferred to ride out to the San Fernando Valley on weekends and shoot jackrabbits from the streetcars. Not that the coast was unpopular; people just had no concept of swimming in the waves. What we think of as “beach culture” was still alien to Americans.

But Huntington had been to Waikiki. He knew that a man who could “walk on water” in the shore break, who looked half-exotic and bronzed in his swimming costume, who had lifesaving skills to match his surfing talent — why, a man like that could lure people to an otherwise empty stretch of sand.

Within days of his arrival in California, Freeth went surfing off Venice Beach. A local paper ran an article on July 22 — “Surf Riders Have Drawn Attention.” This may have startled Huntington, and by the end of the year, Freeth was on the Pacific Electric payroll, surfing twice a day near a section of Redondo known as Moonstone Beach, where semiprecious stones lay in a natural mound along the waterline.

So Jack London’s handsome “brown Mercury” walked up and down a heavy plank in sloppy Redondo whitewash while tourists in Edwardian suits browsed a mound of colorful surf cobble for “excellent specimens” to offer to their sweethearts. Clanking streetcars and an improbable Moorish pavilion gave the once-industrial coastline a carny atmosphere that must have seemed as ridiculous in 1907 as it does a century on, wherever old boardwalks or pleasure piers compete with the roar of the sea. But surfing — professional or paid surfing — had arrived in America, and George Freeth would be more than just a sideshow freak.

* The Freeth sculpture was stolen in 2008 and replaced in a slightly different location.

Michael Scott Moore

Rafts of the Medusa

Why every day on the Mediterranean is a new scandal for Europe. For both Foreign Policy and Die Zeit.

California’s Attempt at Land Reparations

How land seized from a Black family 100 years ago may be returned. The Bruce’s Beach story from a hometown angle, for The New Yorker

Day of the Oprichnik, 16 Years Later

The novelist Sorokin, the president Putin, his man Dugin, and the war in Ukraine. For n + 1.

The Rushdie Narrative

Knife and the crumbling ground beneath free speech

There Must Be Some Way Out of Here

An essay on Bob Dylan, “All Along the Watchtower,” and Somali pirate captivity.

That Mystic Shit

The life of Lou Reed in two biographies

Cambodian Seafarers Talk About Pirates

Mike visits Cambodia for The New Yorker to talk about a harrowing shared experience in Somalia

The Muslim Burial

Cambodian hostages remember digging a grave for one of their own. A sequel chapter to The Desert and the Sea

The Real Pirates of the Caribbean

Adventure journalism in Southern California. A travel essay for The Paris Review.

Antifa Dust

An essay on anti-fascism in Europe and the U.S., for the Los Angeles Review of Books

Was Hitler a Man of the Left?

A book that helped Republicans in America lose their damn minds.

Ghosts of Dresden

The Allied firebombing of Dresden in 1945 destroyed the baroque center of what Pfc. Kurt Vonnegut called, in a letter home from Germany, “possibly the world’s most beautiful city.”

George Freeth, Biographed

The first academic treatment of America’s surf pioneer. Also, was Freeth gay?

It’s Called Soccer

Americans live on what amounts to an enormous island, defended on two shores by the sea, and we’ve evolved a few marsupial traditions that nobody else understands.

Tilting at Turbines (in the Severn River)

The morning was clear and cold, with frost on the church steeple and the cemetery grass. I had a quick English breakfast at a white-cloth table, in my wetsuit, and drove to Newnham, a village on the Severn River in Gloucestershire, parking near the White Hart Inn.

The Curse of El Rojo

I’d packed the car lightly — a bag of clothes, a bag of cassette tapes, a backpack of books, a few essential tools.